Veganism seems to have evolved to become much more about a belief system, than what people chose to eat. It has become almost impossible to have a conflicting opinion without being exposed to the depressingly familiar trajectory of vitriol that follows.

Part 1 of this series investigates, from an anatomical and physiological point of view, what humans are adapted to eat.

Veganism

The main spheres of this belief system, the nutrition, moral and environmental arguments, often entangle when in deep conversation. Most vegans start off in one sphere, then strengthen their belief by adopting the others. Vegans adopt a plant-based diet, avoiding all animal foods such as meat (including fish, shellfish and insects), dairy, eggs, and honey; as well as products like leather and anything tested on animals.

This is my attempt to disentangle the sphere that I feel most confident to engage in – the nutrition argument. I am wise enough to refrain from venturing, in any meaningful depth, into the moral argument. I have grown to understand that the presence or absence of evidence, to a large extent, does not affect peoples beliefs. Everyone is entitled to eat exactly what they wish. I respect peoples choices and do not begrudge them. By the same token, I expect, as a meat eater, to be respected for my choice.

I do not believe that one can be optimally healthy, long-term, on an exclusively plant-based diet. This stance is based not only on my extensive research but on my clinical experience too. All my vegan clients, bar none, exhibit nutrient deficiencies that my non-vegan clients do not. It has become increasingly difficult to ignore objective measurements. I do not believe that veganism is an optimal way of eating.

A good place to start is to try to determine, anatomically and physiologically, whether we – humans – are carnivores, herbivores or omnivores.

FACT

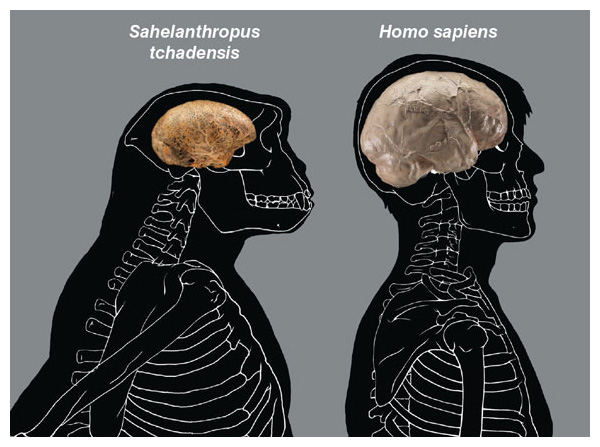

Modern-day humans have much bigger brains compared to early humans.

A Bigger Brain

Over the past 4 million years, the hominid brain has undergone immense increases in size; from 400cc to 1,400cc. We know that all living things have a finite energy budget. We also know that the brain is a very expensive organ, in metabolic terms. How does a brain get bigger in the context of finite energy allocation? A large brain is a considerable metabolic investment. Where did the energy come from to fuel the growing brain? One could be forgiven for assuming that there was a correspondingly higher basal metabolism relative to increases in brain size, but no correlation has ever been observed.

Hominid – any member of the group consisting of all modern and extinct humans and great apes (including gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans) and all their immediate ancestors.

The Expensive Tissue Hypothesis seeks to explain this apparent paradox. It is proposed that the increase in brain size in humans is balanced by an equivalent reduction in the size of the GI (gastro-intestinal) tract. The Expensive Tissue Hypothesis first proposed by Aiello and Wheeler in 1995, states that ”an increase in the size of a metabolically expensive tissue is offset by a decrease in the size of other metabolically expensive tissues”.

In other words, the increased energetic demands of a relatively large brain are balanced by the reduced energy demands of a relatively small GI tract. This relationship also seems to hold true in other primates. Early hominids were a large-bodied species. It would have been challenging to provide themselves with sufficient quality food to permit the necessary reduction of the gut. It is highly unlikely that veganism would have been adequate.

Evolution of the Hominid Brain | INSULEAN

It is estimated that the (mass-specific) metabolic rate of the brain is 9 times that of the entire human body. The brain cannot store a significant amount of energy. A large-brained mammal must be capable of continuously supplying the brain with the substantial amounts of substrate and oxygen required to fuel this energy expenditure.

As well as the brain, the heart, kidneys and splanchnic organs (liver and GI tract) are the four other highly metabolically expensive organs. Together with the brain, these organs account for 60-70% of the total BMR (basal metabolic rate), despite only contributing to 7% of total body mass.

A Smaller Gut

When human organs are compared to those of a similarly sized primate, the heart and kidneys are sized about the same. However, the GI tract is only 60% of that expected. It appears that the increase in mass of the human brain is balanced by an almost identical reduction in the size of the GI tract; and that these changes evolved simultaneously. When metabolic, rather than size relationships were looked at, the energy saved by having a smaller gut was almost the same as that required for a larger brain.

This theory is fascinating, as it suggests that from a metabolic point of view, the primate either has a large brain, or a small gut – but not both.

The heart, liver, and kidneys are tightly related to body size and would have adapted to support the growing brain, ensuring an adequate supply of oxygen and energy substrate. It is highly unlikely that they could vary inversely, in relation to brain size. Unlike the heart, liver, and kidneys, the size and structure of the gut is strongly determined by the diet. This further supports the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis. It made sense for the gut to be ‘sacrificed’ and explains its inverse relationship to brain size.

Veganism – Humans are Meat Eaters.

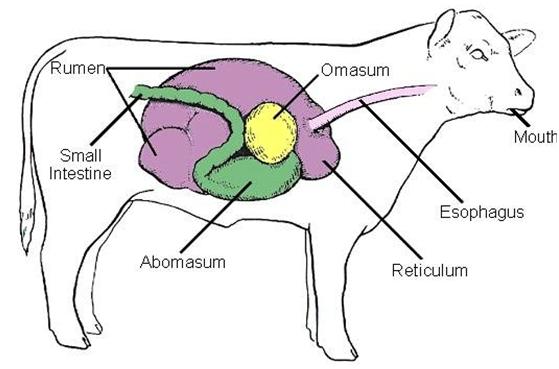

Herbivores, particularly folivores like cows, have large and complex ‘stomachs’ (fermenting chambers). They eat, almost exclusively, large amounts of grass which is very difficult to digest – hence the fermenting chambers which are full of huge colonies of bacteria. Conversely, carnivores have simple stomachs and proportionately longer small intestines. They eat small quantities of highly digestible meat.

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM OF A COW | INSULEAN

Folivores are herbivores that specialise in eating leaves.

If dietary quality determines the size of the gut, a high-quality diet must be essential for a large brain. It therefore follows, that to permit the necessary reduction of the gut, early hominids would have had to increasingly rely on animal-based foods, which are less voluminous and more rapidly absorbed.

There are, of course, other factors that could have been responsible for the expansion of the hominid brain. These include a combination of social intelligence, more sophisticated foraging behaviour necessitated by a high-quality diet, locomotor factors (such as bipedalism) and adaptation to climate variability.

It is highly probable that we developed a large brain by evolving a smaller gut. This simultaneous change was necessitated by an improvement in dietary quality. To do this, our ancestors must have relied more and more on animal-based foods.

Veganism, therefore, is not our heritage, and cannot be our destiny.

In Part 2 of this series, I argue that the length of our colon (large intestine) reflects an adaptation to a predominantly carnivorous diet, but that we have thrived as a species by being opportunistic omnivores.